Nomads, outsiders, storytellers. In The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt, cultures shaped by wandering and marginalization bring flavor and friction to the world of the Continent. Among them, none stand out more than the traveling communities that mirror the real-world tsigane people—Europe’s historic Romani populations. While Geralt’s path is often solitary, it repeatedly crosses with groups who echo this long-suffering, misunderstood minority.

This article explores the tsigane roots in real history—and how The Witcher 3 channels their presence through in-game cultures like the Ofieri and other nomadic peoples.

Who Were the Tsiganes?

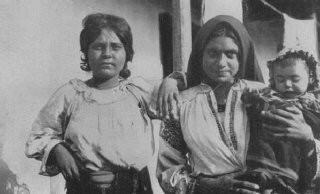

Long before Europe’s kingdoms rose and fell, the tsigane (or Romani) people had already begun their journey. Originally from the Punjab region of northern India, they migrated to Europe between the 8th and 10th centuries. Misunderstood and mislabeled—often called “Gitans” in France (from egiptano, suggesting a mistaken Egyptian origin)—they developed into a network of diasporic communities across the continent.

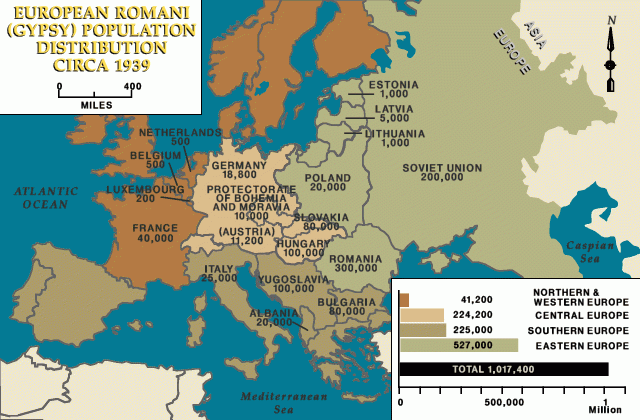

By 1939, an estimated 1 million tsiganes lived across Europe. Nearly half resided in Eastern Europe, especially in the Soviet Union and Romania. In Greater Germany, around 30,000 lived as citizens, including 11,200 in Austria. Despite being part of society—working as artisans, musicians, tradesmen, and even civil servants—many were still seen as outsiders.

The Witcher’s World and Real Margins

The Witcher universe isn’t a one-to-one historical setting, but it thrives on allegory. Racial tensions, regional politics, and displaced peoples feature heavily in the narrative. While the game doesn’t explicitly label any group as tsigane, the portrayal of nomadic tribes—especially the Ofieri visitors or the traveling circus folk—clearly borrows from Romani traditions.

In Hearts of Stone, Geralt meets the Ofieri, a wandering people from a far-off desert land with rich oral traditions, elaborate clothing, and deep mysticism. Their music, rituals, and magical items evoke the exoticism often associated—sometimes problematically—with tsigane culture. They are seen as both fascinating and foreign, respected for their skills but mistrusted by locals.

This reflects the double-edged perception tsiganes faced in Europe. Seen as musicians, blacksmiths, and performers, they were also scapegoated, stereotyped, and persecuted—sometimes by the same communities they served.

Nomads, Identity, and Mobility

In-game and in history, mobility is both freedom and threat. Many tsigane communities in the early 20th century were no longer fully nomadic but maintained seasonal travel for work—especially in agriculture or entertainment. They balanced integration with preservation of identity.

In The Witcher 3, several side quests and stories feature transient characters—wandering healers, traveling merchants, or even cursed performers. These characters often hold crucial secrets or serve as catalysts for moral choices. Their liminal status grants them knowledge of many worlds but full acceptance in none.

This echoes the real tsigane experience: a people rooted in Europe for centuries but rarely given the space to belong.

Numbers and Spread: The Tsigane in Prewar Europe

Let’s break down the demographics that defined Europe’s Romani population just before WWII:

| Region | Estimated Tsigane Population (c.1939) |

|---|---|

| Eastern Europe (USSR, Romania) | ~500,000 |

| Greater Germany | ~30,000 (including 11,200 in Austria) |

| Western Europe | Smaller, scattered communities |

| Balkans (Hungary, Yugoslavia, Bulgaria) | Significant populations |

The term tsigane was used broadly across languages, although many preferred identifiers like Sinti or Gitans. They spoke dialects of Romani, rooted in Sanskrit, and practiced a variety of religions shaped by centuries of migration.

The Word Behind the Stigma

In German, Zigeuner comes from a Greek root meaning “untouchable” or “pariah”—a reflection of centuries of exclusion. Despite their integration into trades, art, and even bureaucracy, tsiganes were viewed with suspicion.

In The Witcher 3, this prejudice is echoed subtly. Foreign characters are distrusted. Traders from far lands are accused of thievery or witchcraft. Even when Geralt helps them, they often remain on society’s fringe. The developers don’t spell out the history, but the social echoes are clear to those who know.

Magic, Music, and Margins

Many tsigane were known for their talents: animal training, music, smithing, and mystical arts. In the game, characters with similar backgrounds are often tied to folklore or magic. One can’t help but notice the thin line the game walks between homage and exoticism.

Is this portrayal fair? That depends. On one hand, The Witcher 3 gives these characters agency, dignity, and narrative weight. On the other, they’re often reduced to their otherness. Just like real tsigane, they’re present in the world—but rarely at the center.

Why This Matters

The way we write stories—especially fantasy—shapes how we understand real-world cultures. By recognizing the roots of groups like the tsigane, we can appreciate their contributions, challenge lazy stereotypes, and foster empathy.

The Witcher 3 invites players to walk among outsiders, solve their problems, and sometimes join their rituals. That narrative choice brings us closer to the historic tsigane experience than we might expect.

A Player’s Reflection

“I used to see Ofieri as just flavor. Then I read about the real tsigane—what they lived through, how they traveled, what they meant to Europe. Now every time I ride into a village in Velen, I wonder whose story isn’t being told.”